This article was originally published by the Massachusetts Horticultural Society’s Leaflet, January 2024 Issue

In First Person

Written by: Russ Cohen, ELA Member

For more than 50 years Russell Cohen has been involved in numerous environmental communities and endeavors, uniquely bestowing his energy and personal resources to help people understand and appreciate the value of nature. Russ has pioneered “re-indigenizing” the plant life in public gardens, landscapes, and environmental sites in this region, specifically applying his knowledge on more than 190 species of edible native plants. Here’s Russ’ story, outlining his passion and why it has become such a driving force in his life.

I grew up in Weston, MA (where my mom still resides), spending lots of time in the woods, cultivating a strong spiritual connection to nature. As a sophomore at Weston High School, I enrolled in a biology department mini-course called “Edible Botany“: my first formal exposure to edible wild plants. We learned about two dozen edible species that grew around the high school grounds, and the class finished with a “big feed”: a communal meal prepared from these plants.

Inspired by this experience, I took out every book I could find on the topic from the Town library, taught myself about dozens of additional species, and, then, as a high school senior in 1974, I taught the same Edible Botany class I had taken as a sophomore.

While in college, between my sophomore and junior years, I spent a summer at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, MA, enrolled in an intensive course called “Plants in Relationship to Their Environment”. It was in the midst of that course, when I was asked to come up with a topic for a term paper, that I had an epiphany of sorts: not only did I know what that term paper would be about, I saw my whole career path in front of me, like Moses looking into the Promised Land. That career would be the conservation of land in its natural state: not just for its intrinsic value, but for also its value to humans. Basically, I was motivated to preserve open space so it would be available to people to be in: to experience the restorative and recuperative power of nature as I have.

Continuing my undergraduate education, at the University of Michigan and Vassar, all of my elective course work and writing was focused on some aspect of land conservation. For example: the subject of my senior thesis at Vassar was on Vassar Farm: a 500+acre parcel of mostly wild land that the College was contemplating divesting itself of at the time. I have been told that my thesis helped persuade the College to keep the Farm, and it eventually became an ecological preserve.

My focus on land conservation continued in graduate school at Ohio State, where I received degrees in law and natural resources, while in the intervening summers worked for nonprofits engaged in land conservation, such as The Nature Conservancy, Mass Audubon and the Land Trust Alliance. My first full-time job was running The Hillside Trust: a land trust focusing on conserving the undeveloped hillsides surrounding the City of Cincinnati, OH. While there, I enjoyed encountering and nibbling on the wild edible flora of that region, which included some more southerly species I had heretofore not encountered, like Persimmons, Pawpaws and Passionfruits.

Tupelo (aka Black Gum, Nyssa sylvatica), a native species suitable for planting in riparian areas. The berries’ tart flesh can be used for sauces, jelly or jam.

After eight years in Ohio, I longed to return to my “home” landscape of New England, so I moved back here in the late 80’s. I eventually filled the position of Rivers Advocate with the Mass. Department of Fish and Game, working on river and stream conservation, with a focus on riparian land protection. One of the outreach materials I produced there was a list of native species suitable for planting in riparian areas, all of which were suitable as food for wildlife and humans. My proudest achievement in that role was the drafting and passage of the MA Rivers Protection Act in 1996, which established a 200-foot-wide protected area of natural vegetation along all perennially-flowing rivers and streams in the Commonwealth. It is among the strongest laws of its kind in the U.S., and seems especially prescient now, as our understanding of the importance of naturally-vegetated riparian areas for habitat connectivity, and the need for our waterways to be resilient to the effects of climate change, continues to grow. (The August 6th bill-signing ceremony in Allston is remembered by many living in Massachusetts at the time; not for the substance of the legislation, but for what Governor Bill Weld did afterward: he dove into the Charles River, a stunt that made the national news).

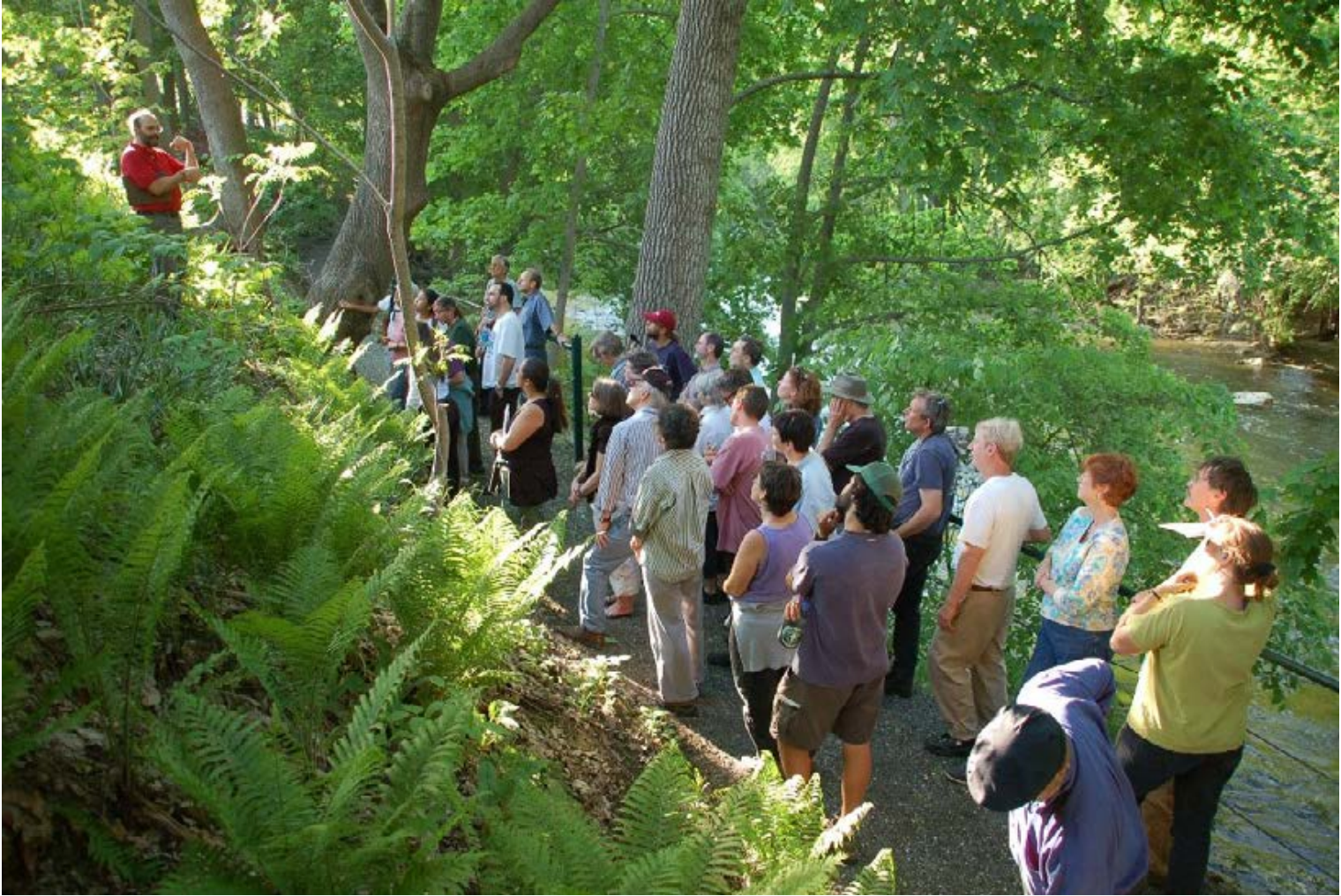

Russ leading a wild edibles walk along the Housatonic River, Great Barrington, in May of 2006. The Housatonic is one of the waterways covered under the Rivers Protection Act of 1996. photo by Rachel Fletcher

In the meantime: while fully engaged in this work, I continued pursuing my passionate avocation: connecting to Nature by respectfully and gratefully partaking of its edible gifts. (It’s my form of Communion: not wine and wafers, but the consecration of Nature via nibbling on wild berries, nuts, etc. and/or the things made from them; it’s basically the same concept.) In fact, there was often good synergy between my job and my foraging hobby, as my work often took me out into the field, and before or after my official work was done, I’d be out with my foraging basket, collecting whatever happened to be in season at the time. And, in addition to this, each year I would lead dozens of wild edibles walks and talks for a variety of sponsors throughout New England and eastern New York State. In the meantime, my foraging book, entitled Wild Plants I Have Known…and Eaten, published by the Essex County Greenbelt Association, came out in June of 2004, will soon be reprinted for the ninth time.

It was in the fall of 2013, well into my third decade as the state’s Rivers Advocate, and looking ahead to my eventual retirement, that I had the first glimpse of what would eventually evolve into another epiphanic vision of what I could do next. It was triggered by the Shagbark Hickory, my #1 favorite wild edible: a species whose delicious nuts I love to gather and share with others, in the form of delectable baked goods, or simply toasted a few minutes in a toaster oven. I gather thousands of hickory nuts every fall, and have, by keeping track of where they are in the landscape, located enough shagbark hickory trees that, even if some are taking a year off from nut production, I will know of others that aren’t, and so am always able to have a successful harvest. So, that fall, brimming with gratitude for another fruitful (or should I say “nutfull”) season, as I perused the dozens of bags of foraged hickory nuts I had collected, it occurred to me that I should be returning Mother Nature’s generosity in the form of setting aside some of my harvest: not for eating, but for propagating into new trees, by myself and others. So I gave away many of the nuts I had collected for that purpose, ranging from organized groups with deep experience in growing native plants from seed, like the New England Wild Flower Society (now the Native Plant Trust), to novices just learning the basics of plant propagation, like members of the recently-formed (in 2010) nonprofit Grow Native Massachusetts.

By the spring of 2015, a clearer and broader vision of what I would take on as my “next act” began to emerge. While continuing to carry on my usual load of several dozen wild edibles-themed walks and talks, I could also play the role of a modern-day “Johnny Appleseed”; not for apples (which, as you probably know, are not native to the Western Hemisphere); and not just for Shagbark Hickory; but for all the plant species deemed native to Northeast ecoregions that are edible by people. So, on my collecting trips that year (and every year thereafter),in addition to gathering wild edibles for eating, I would gather the seeds of native edible plants, for propagating myself, or sharing with others for growing on their own.

“Why confine yourself to just native edible species?”, you might ask. Of course, horticulturalists and other “plant buffs” have developed countless varieties of cultivated edible plants, seeking to improve (in terms of size, yield, etc.,) beyond what is already available, and are avidly adding these plants to home and other landscapes, like permaculture plots and “food forests”. I am generally supportive of this trend, and happy that the idea of edible landscaping is gaining acceptance in communities that heretofore looked at fruit- or nut-bearing plants in public spaces as a nuisance. And, on the other end of the spectrum: while many of our weeds and invasive species are quite tasty, and I happily extol their comestible virtues during my walks and talks, these species are doing well enough (perhaps too well, in many cases) in proliferating on their own to need any help from me.

What I see my niche to be is to confine my seed collection, propagating and planting to straight-species native to Northeast ecoregion plants that are edible by people, and to especially look for opportunities to return these species to landscapes where they once were present, but were extirpated in the course of the European settlement of New England in past centuries, and the conversion of natural plant communities to farms, pastures, tree plantations, etc. As it turns out, there are over 190 species of plants that meet these criteria (see the list I have compiled at this link), so it’s a pretty big palette to work from.

So this role: the “Johnny Appleseed” of edible native species, is what I am now doing as my primary post-retirement pursuit. It is an expression of gratitude on my part: a way to give back to Mother Nature in thanks for all the gifts of wild edibles she has generously provided me over a lifetime of foraging. I have set up a nursery in Weston, near where I grew up, where I am growing over 1,000 plants, consisting of a subset of the 190+ native edible species from my compiled list. In case you’re wondering, I do not operate this nursery as a business; I give away all the plants I am growing there. That said: my primary intention for these plants is for them to be planted in publicly-accessible locations, where the public can see and interact with (including, if the rules governing that site permit, harvesting to eat) them. While I am not intending my plants to end up in private yards, I might consider a barter in exchange for some help at my nursery.

Click here to read Russ’s guide!

So I have followed this process, or something like it, for diversifying properties with native edible plants, for over two dozen sites in the last eight years. These include (in Massachusetts): the Essex County Greenbelt Association’s Cox Reservation in Essex; the Town of Lexington’s Willard’s Woods conservation land; the former lighthouse station on Bakers Island in Salem, maintained by Essex Heritage; Crowninshield Island in Marblehead, maintained by The Trustees of Reservations: Holly Hill Organic Farm in Cohasset; Wheaton College, in Norton; River Walk in Great Barrington; and the Acton Arboretum.

Russ, with a Black Birch (Betula lenta) from his nursery, ready to plant it as part of the Miyawaki Forest Project, Cambridge, MA, September, 2021. Photo by Maya Dutta.

How have my plantings done, at these and other sites? Well, it’s been a mixed bag, ranging from complete failure (none of the plants I put in are still there) to 70% or more survivability, which is a very satisfactory outcome indeed. I set a low bar for success on my projects, though; if even a relative few of the many plants I brought to a site do well, that’s nevertheless very gratifying. One of the most pleasing aspects of this work is encountering a plant on a site where I have planted it that is thriving. I feel like I can read that plant’s mind, and it is sending me a message: “Thank you, Russ, for planting me here; I am very happy here.”

If you find any of this appealing, please view my online biography for more information, or contact me at eatwild@rcn.com or 781-646-7489.